Rose Art Museum, Brandeis University 1986

fir, stone, concrete

18′ x 23′ x 23′

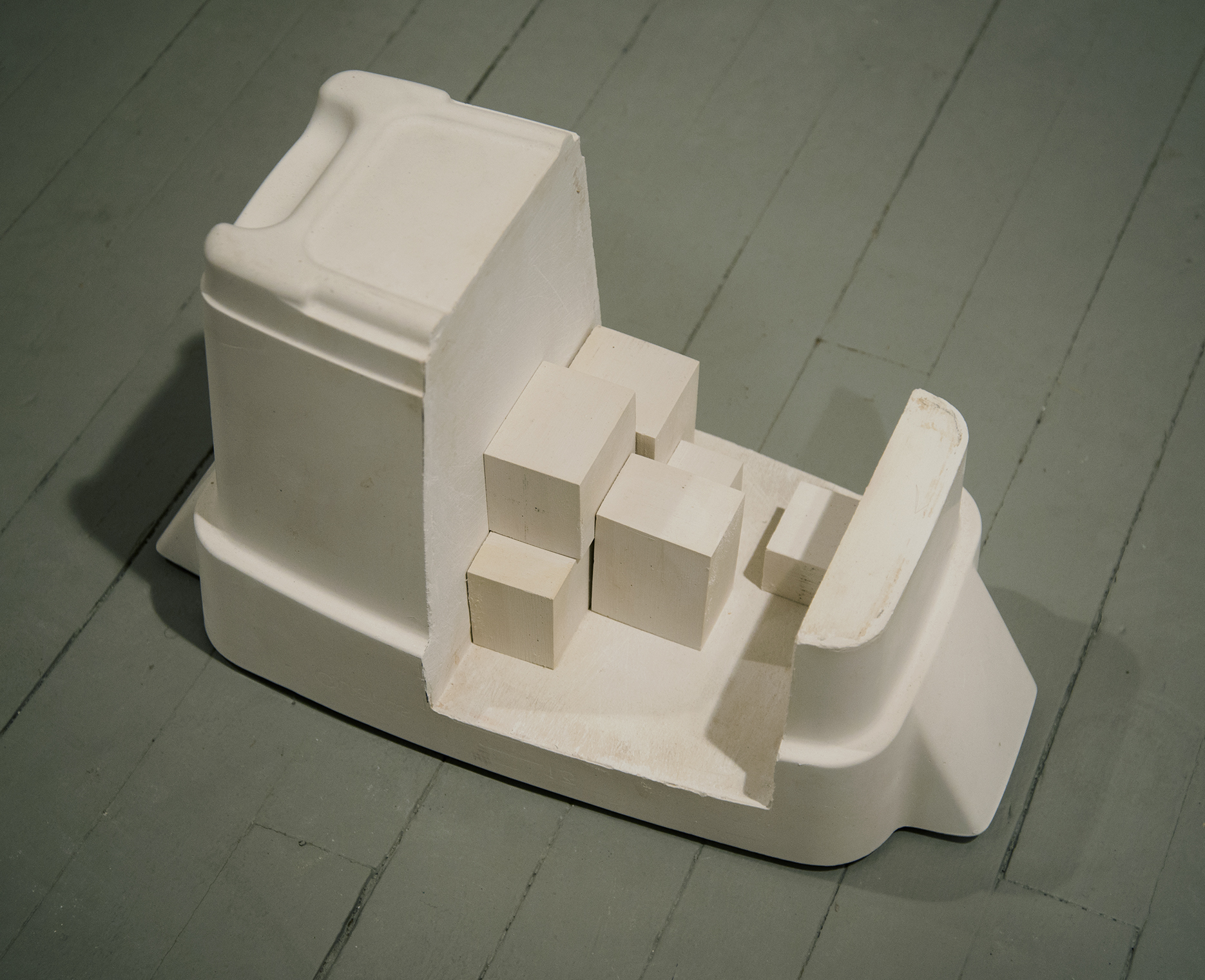

A platform constructed within the gallery architecture, High Mesa is an archetypal artist’s dwelling. A small boulder and cast stair steps up from the gallery’s travertine floor to an elevated wooden platform that embraces and penetrates the gallery architecture. A thickened and bleached wooden area marks a place of repose before a window onto the landscape. A cast plaster well penetrated by burnt tree branches forms a hearth; and an opening cut into the floor overhanging the gallery stairwell and a pool of water below marks a vertiginous well.

ROSE ART MUSEUM

Brandeis University

High Mesa: a plateau atop a Cliffside, looking out over a landscape vista and down onto a spring below. As envisioned by sculptor Jeffrey Schiff, these are nature’s counterparts to the architectural elements of the museum’s topography, specifically floor, staircase, window and pool. Built into this visionary landscape he has conceived and constructed a dwell: a minimal archetypal living space with floor, bed, hearth and well. So begins our journey though Schiff’s sculptural environment where sensations are unlocked and visions inspired – quietly and slowly over time.

In the coexistent realities that are revealed and the rich overlays that emerge between nature and architecture (museum, mesa and dwelling), natural and man-made materials (branches, stone, lumber, concrete), and the interplay between pre-existing and newly created spaces forms, we discover multiple references to the complex layers of meaning and experience common to any environment we encounter during the normal course of our daily lives.

Likening the dwelling to an artist’s studio, Schiff sees this sculpture as a holistic environment dedicated to the creative process itself. He has constructed three distinct but integrated physical spaces, each designating a particular type of function or behavior. Our passage from one space to another is across an elevated wood floor, accessible via three steps made of natural stone and concrete. There we encounter these forms: a bed – a restful contemplative place belonging to the interior but visually connected to the outside; a hearth (whose charred branches are evidence of atleast a singe use) – a place where a creative process is enacted and physically realized; a well – an extension of a safe interior space to a possibly dangerous exterior one.

With High Mesa, Schiff puts us in touch with our own physical presence in known and unknown spaces and explores the complex but delicate interplay of form, space, perception and experience.

THE BOSTON HERALD, Sunday, March 23, 1986

New Works by N.E. Sculptors

Rose Museum exhibits run from the highly finished to the playful

By, Nancy Stapen

“Sculptural objects and Installations: The Lois Foster Exhibition of Boston and New England Area Artists” – the 10th annual exhibition at the Rose Art Museum at Brandeis University – is presenting new work by local artists.

Previous shows have concentrated on new talent, but this year, museum Director Carl Belz has created an elegant and unusual show of six sculptors with established reputations.

Works by most of these artists are rarely seen in Boston. The size, scope and ambition of such artists as Jeffrey Schiff, Jim Coates and Eric Lintala make museum and gallery exposure difficult.

Even for orthodox artists, sculpture is difficult to market. It’s expensive, often unwieldy and occupies a lot of space. That intimidates many collectors.

In this high-caliber show, the Rose offers a range of work – from highly finished to playful and transitional.

For some contemporary sculptors, the reference point remains minimalism – the austere, repetitive style that held sway in the 1960s though early 1970s. But in the late 1970s, sculpture went in many directions. The styles included object-oriented, figurative, architectural, found object and installation. All may be characterized as post-minimalist directions.

Jeffrey Schiff’s evocative installation “High Mesa” is a sophisticated, complex work. Lodged in the left corner of the top-floor gallery, it convinces on formal, architectural and psychological levels. It combines sensitivity to the airy, horseshoe-shaped upper gallery, which overlooks an interior pool and fountain, with knowledge of the woodlands surrounding the Rose.

Sprawling horizontally in the back corner, a raised platform of blond wood (Douglas fir) is divided by suggested furniture into three areas. A bleached wood “bed” is laid below the floor-to-ceiling corner window. On a sunny afternoon, the bed is flooded with light, inviting the outer world of nature into this interior space of architectural shelter. Behind it, a 48-inch concrete square pierced by charred branches suggests a hearth or kitchen.

In a brilliant manipulation of space, Schiff has cantilevered a corner of the platform over the balcony, which itself becomes an integral element o the piece. From a precipitous vantage, the viewer may gaze down though a 2-foot cut-out square, an image suggesting an exterior well.

More straightforward is Jim Coates’ “The Rose-Lean-to Installation,” in which a set of three large triangular wood-and-rope structures evoke primitive dwellings.

Eric Lintala’s “Perimetric Containment,” which turns a downstairs gallery into an imaginary, desertlike environment, is enclosed yet expansive. Lintala has divided the room into triangular vistas of sand that hug the wall, supported by waist-high wooden constructions. The beige brown painted wood and warm color of the sand softened by atmospheric lighting result in an earth, meditative ambience. Lintala’s manipulations of perspective produce an illusion of swelling and contraction.

The three object-oriented sculptors explore distinct concerns. Howard Ben Tre’s cast glass-and-copper columns have a majestic presence. Based on simple, industrial forms, these have the clearest relationship to minimalism. Still, their evocatively textured surfaces, fanciful capitals and variant bases provide a wealth of visual detail.

George Creamer’s whimsical, pastel-painted branches juxtapose a polished, highly finished surfaces with the quality of a nervous gesture. These works achieve a lank humor when placed directly on the floor. They become sensuously elegant when placed on pedestals.

Lastly, Mags Harries is Boston’s best-known public sculptor, both for her Haymarket installation and more recently Porter Square “Glove Cycle.” She shows wall reliefs that playfully take apart the objects they depict. Plastic replicas of fruit, mugs and travelogue trays are split open and titled upward in a collaged cubist pun. (Through April 13)