1998-2002

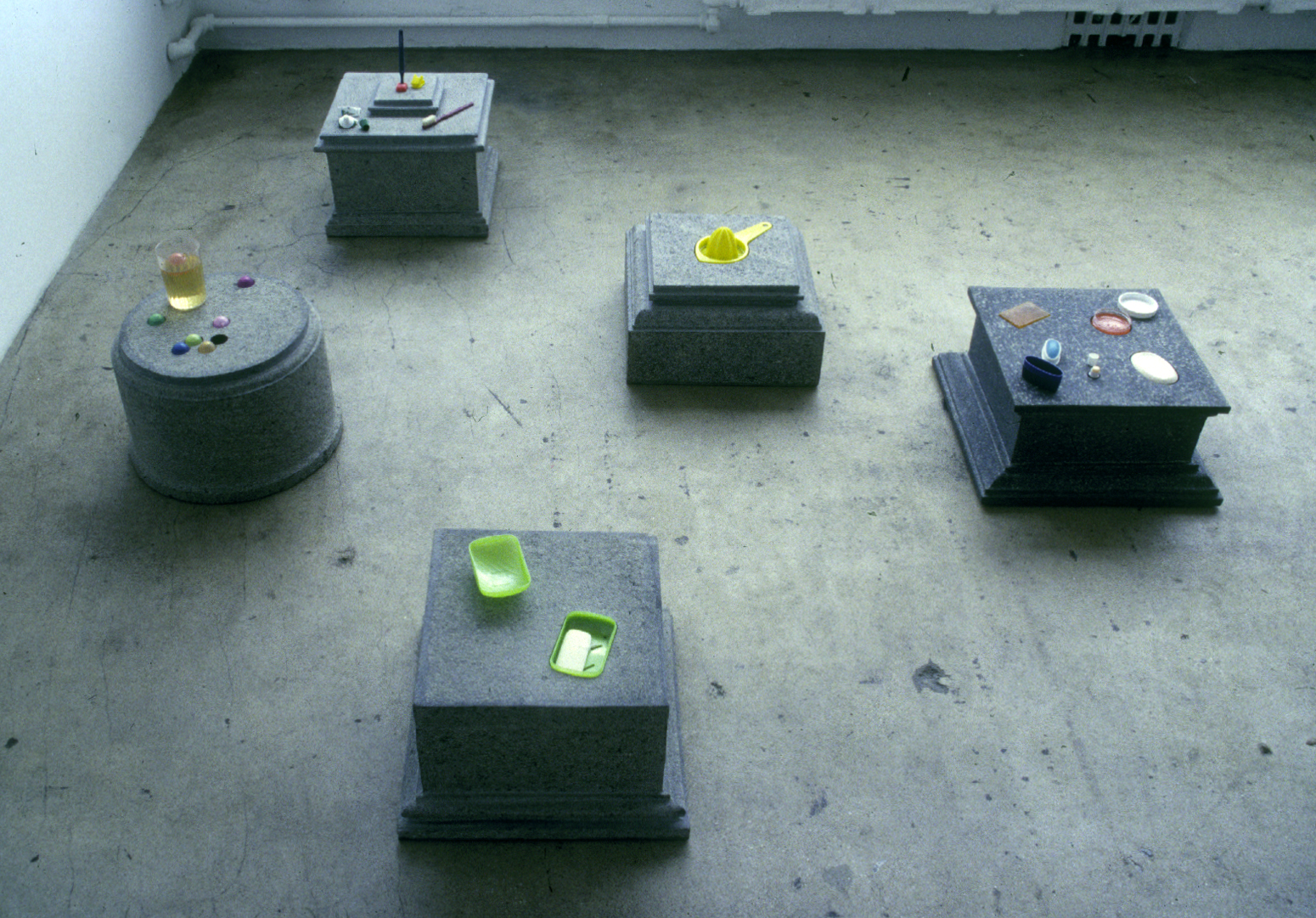

black granite, household objects (soap, plastic kitchenware, sponge, etc.

Variable Dimensions

In Everyday Chidambaram, granite plinths, based on details of Indian temple architecture, were customized to house the disposable objects of daily rituals—plastic containers, soaps, toothbrushes, sponges, etc––embedded into the stone mass.

Everywhere Chidambaram catalogue essay

Everything Everyday

by Peter Nagy

Many artists travel to foreign countries and become inspired by their cultures. Often, this results in the artists incorporating visual motifs or found objects from these cultures into their works. Often, the results are only superficial references to these cultures or, at worst, they can be blatant misappropriations for the sake of exotic novelties. It is rare that an artist can come away from a preliminary encounter with a foreign culture with perceptive insights. It is even more rare when one is dealing with a culture as overwhelmingly complex as is that of India.

Insight came to the American artist Jeffrey Schiff during his first visit to India as a Fulbright scholar in 1998. By patient observation, research, close attention to detail and careful listening, Schiff made sculptures which achieved what all artists aspire to create––works which transform materials into signs loaded with meanings, which have resonance, physical presence, and a poetic sense of transgression which may come as a surprise to even the artist himself. Yet this suite of works created in India dovetails elegantly with Schiff’s other works to date, being no radical rupture from his sculptural program before or since, and in that way appears effortless, natural and personal, as the best art usually does.

By employing Ayurvedic soap and the multiple organic elements used in Hindu ritual practices in his works Everywhere Chidambaram and Everything Chidambaram, Schiff obviously refers to traditional Indian religious contexts. Likewise, he spells out with letters cut from blocks of the soap a medieval Tamil poem of sacred purpose. Yet his use of soap and his insistence that the viewer of his works washes his or her hands, in sequence, with the letters of the poem (the work, self-contained, even provides the water and hand towels to do so) moves one away from the purview of the rarified and sacred and into the realm of the quotidian and secular. By so doing, the works comment on this sacred/secular divide within Indian society, a divide which has gained an increased urgency of late as it has become a locus of contention in the political arena and for the nation’s image of itself. Likewise, Schiff’s works comment on the thin line separating an almost neurotic attention to detail operative in sacred ritual practices in the temple and its reflection to be found in obsessive behaviors in the home. Many visitors are drawn to comment upon, though few residents seem to notice, the glaring disparities between private cleanliness and public slovenliness found throughout India. Bathing, washing and the policing of cleaning reach almost a fever-pitch in many Indian homes but only recently is this beginning to be transferred into a concern for civic amenities or the natural environment. Schiff’s works touch on these multiple issues hesitantly, as if to admit that he is opening a Pandora’s Box of references of which he has neither the experience nor knowledge to properly ascertain.

With the group of works Everyday Chidambaram Schiff finds another route to examine this often irrational split between sacred and secular practices. By logical extension, should not the brushing of one’s teeth or the washing-up of dinner dishes also be pious acts? Schiff seems to imply so by creating granite plinths in classical styles to serve as bases for the most mundane of household objects. These monumental and ludicrously permanent mounts for disposable plastics poke fun at the proliferation of “designer” objects which now encompass every category of consumer goods in the western world, a flood of commodities which is rapidly entering the Indian marketplace. Conversely, the daily rituals of every man, woman and child are afforded the same framings as the most esoteric practices of ascetics and priests.

Schiff’s Chidambaram works refer to the sacred city of South India which Hindus believe to be the center of the universe. It is there that the god Shiva, in his form as Nataraja, planted his right foot when he danced the dance which brought light and life to the cosmos. Schiff’s sculptures use Chidambaram only as a starting point, a site to anchor a stand, to locate a work which is not about the place per se but about India as a whole, a generalization perhaps, but one which is purposefully open-ended and obtuse. Chidambaram, as both a sacred site and a living city, can be used as a metaphor for a wider arena, for a way of thinking, for an approach to art. This “approach” is what the artist came to India looking for: a self-conscious investigation of modes of living and patterns of behavior which could be applied to the production of art, caught as it is in the tightening grip of a long historical progression in the western world and sorely in need of escape routes. Schiff’s Chidambaram works attempt to chip away at the sanctimonious preserve of Fine Art in the western world, accommodating the values of both use and decay into the pieces, while piercing the safe haven of secularized art with not religion itself but, more to the point, the ennobling values of devotional practice.

In his exhaustive book which outlines the history, meanings and symbolisms of Chidambaram, the Tamil scholar B. Natarajan refers to the conception of the god Shiva as Nataraja as being the perfect synthesis of science, religion and art. Shiva as the Cosmic Dancer is, he states, “a vivid visualization of the cosmic creation in the unending rhythm of evolution, devolution, creation and destruction in perpetual movement which symbolizes the rhythm of the spirit, primal rhythmic energy underlying all phenomenal appearances and activity.” Together, this synthesis and this unending rhythm conflate all human endeavors into a unified approach and obviate the distinctions between that which is held sacred and that thought of as secular. For Jeffrey Schiff, these insights fostered an opportunity to create works of art which interrogate social conundrums, breach philosophical boundaries and inspire new ways to live creatively.

The color 50-page book Everywhere Chidambaram from Nature Morte Press is available for $12.95 + tax/shipping at Printed Matter Inc., 195 Tenth Avenue New York, NY 10011 T: 212 925 0325, http://printedmatter.org