2003

with James Jacobus, Myra Rasmussen, and Aki Sasamoto

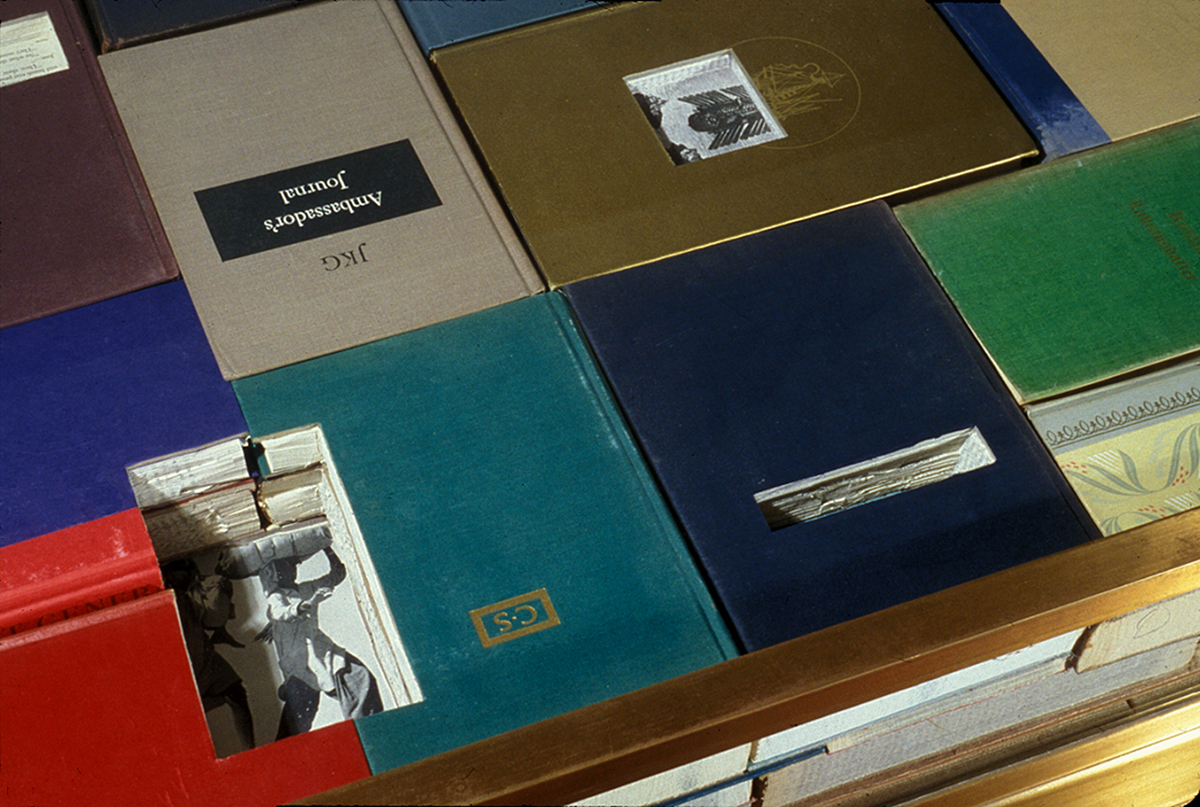

The Library Project is an installation of nine artworks that explore the nature of the library–its vastness, its proliferation, and the peculiarities of its organization. While the Wesleyan University Library is its specific subject and site, the project refers by implication to any and all libraries.

The Library Project began in the Fall of 2001 as a credited, three-student tutorial with James Jacobus ’03, Myra Rasmussen ’04, and Aki Sasamoto ’04 under the auspices of the Christian Johnson Foundation. Later, Wolasi Konu ’04 joined the project as graphic designer. During the semester we worked as a research and development team–researching some of the operations of the library (acquisitions, cataloging, etc), reading relevant texts (Borges, The Library of Babel; Barthes, The Plates of the Encyclopedie; Spoerri, An Anecdoted Topography of Chance), and experimenting with and modeling ideas for works of art about the library. By the end of the semester, we had general plans for an exhibition to consist of several distinct but related works of art in response to the library. For the next year and a half, in fits and starts, we made the works.

We focused our project on the library’s burgeoning scope, and how its profusion of representations organize information and bodies of knowledge. We were particularly interested in the library’s liberal inclusiveness and decisive selectivity, which occludes from sight all that it excludes; the organizational pathways of the Library of Congress classification system which inevitably obscure other possible routes of inquiry; and the general proximities of knowledge–the ways in which areas of knowledge interconnect or self-isolate, whether by accident or design. Ultimately, we were concerned with how the library indexes the world of experience outside of the library. Because the library is now so large and complex a universe unto itself, and so influential on our perception and thought, there appears to be a reversal at work – the world now becomes an index to the library.

THE HARTFORD ADVOCATE, SEPTEMBER 11-17, 2003

Take A Number

An Art Installation at Wesleyan Sends Viewers Back to the Books

by JOHN ADAMIAN

Look carefully when you walk into the grand entrance to Olin Library at Wesleyan University in Middletown. There, among the ornate columns and the hush of study, are call numbers –– the system of letters and numbers used for classifying the library’s holdings –– and they’re not on the spines of books. They’re everywhere. Neat black letters read “ED 1:328/5:L61/4” on a marble bench. On the wall –– “NK 1442.533 2003;” and below an old thermostat is written “QEB S45.” As you walk around campus and further afield into downtown Middletown, you’ll notice more of the peculiar markings popping up in unusual places, on trash bins, in elevators, in bathrooms and at around 500 other spots.

This is not the mad filing work of some potty librarian. The unassuming code is part of a large-scale project –– a reflection on the meaning of the library and the ways we access, consume and relate to information –– by art professor Jeffrey Schiff and three of his students.

Schiff, a sculptor and installation artist, has exhibited everywhere from New York to New Delhi, and he is frequently commissioned to create art fro public spaces. The idea of creating art that is a meditation on the way our culture stores collective knowledge is a recurring topic for Schiff, whose previous work has dealt with encyclopedias and systems of taxonomy.

With the help of three students –– James Jacobus, Myra Rasmussen, Aki Sasamoto –– who were participating in a program that allows undergrads to assist professors with research by providing funding and/or course credit, Schiff and crew set out to think about the role the library serves.

“Together we just started to investigate the library and ask questions about the library, about how enormous it is, how it’s a universe unto itself, and how it’s proliferating at an incredible rate,” says Schiff. “The library at Wesleyan has 1.5 million volumes and it gets 20,000 more a year. [We looked at] how bodies of knowledge are organized within it and how they either exclude each other or they connect with each other.”

This was two years ago. After interviewing librarians, students and professors –– the people who create and use the mass of books, journals, videos, scores and recordings at the library –– Schiff and his collaborators formulated some ideas for actual pieces that would use the library as both a gallery and a theme. In addition to the piece involving the call numbers, Schiff and his students created seven other pieces that explore the themes of books and the worlds that they contain and create. Some of the work is a meditation on the interconnectedness of all knowledge, using as a jumping-off point the idea of the “keyword” search and the way we boil down a vast body of information into smaller and smaller subject headings in order to better process the data.

“The way we think of the library is as an index to the world; the world is larger, the library is concentrated. All these works in some way reference the world,” says Schiff. “Just getting a sense of how vast the library is –– that it’s a universe unto itself –– it occurred to me that that equation can be reversed. In a way, the world becomes an index to the library because the library is so constantly influencing every way in which we perceive and think about the world. Then it seemed inevitable that the way to get to that would be to mark the world in the library’s terms, which is the call numbers.

For the viewer, the piece functions like an Easter Egg hunt of data spilling out from the library out into the campus and the town at large. First you spot one set of call numbers, posted on a window, then another on a kiosk or a wall, soon you realize they’re everywhere. The call numbers are like a kind of hypertext link –– the highlighted connections that bring you to other related sites on the Internet –– in the physical world. And rather than providing specific terse information, like that found on a historical marker, the call numbers simply point to a broader body of information, a book.

“I think for the piece to work, you come upon one, then you unexpectedly come upon another and another, so that you start to see that it really applies to everything,” says Schiff.

At Wesleyan, where the tradition of student chalkings of explicit sexual statements onto campus walkways had created a controversy in recent years, the whole notion of posting writing in public has become contested. And with the university’s president Douglas Bennett banning the chalkings last academic year, some expected students to react to the posted call numbers, but Schiff hasn’t seen any chalked response to the call number postings thus far.

The connection varies between the books and the sites where the call numbers are posted. If one follows the call number posted on the window of the university’s music studios one finds the book If you don’t Go, Don’t Hinder Me: the African American Sacred Song Tradition, by Bernice Johnson Reagon, a singer and scholar of gospel music. The call number under the library thermostat leads you to Medical Thermometry and Human Temperature, a 19th-century text by Edward Seguin.

The task of deciding which titles to use with which sites on campus took a fair amount of research.

“This is extremely open-ended,” says Schiff. “There’s nothing terribly exacting about it. You could have one here, and you could have one there. You could use this book or you could use that book. Because there are all these different ways in which a book will relate to a site, and degrees to which it will. You know, does it hit right on the target, or is it a little more tangential?”

Schiff says the proliferation of call numbers (it took a team of six people working for four days to post them) will hopefully gently jar passersby with the notion that just about any place –– especially the paths we walk by habit every day –– has a history and a story and something that we can learn about it.

“The hope is that there will be this sense of surprise and wonderment and question,” says Schiff. “People will ask ‘What is this and why? And who’s the authority that’s doing this?’ and ‘How does this relate to where it is?’ Hopefully it will wake people up to their environment and make them think about books, and then it’s open for the degree of participation that the viewer wants. They can have all of these different levels of experience. Hopefully all together you’ll have an enriched, more opened-up relationship with the library and what the library represents, which is our body of knowledge.”

THE NEW YORK TIMES, SUNDAY, OCTOBER 19, 2003

A World Surrounded by Numbers

by Benjamin Genocchio

Students returning to Wesleyan University in Middletown this fall were greeted by strings of letters and numbers, on walls, doors, flagpoles, windows and even trees all over campus. Similar markings were also spotted at sites in the nearby town, like O’Rourke’s Diner, on Main Street, the Neon Deli and the Destina Theater.

The letters and numbers are not a sinister message from another galaxy. They are part of an art installation by Jeffrey Schiff, a professor at Wesleyan, in collaboration with three students. Each of the strings, and there are over 500, corresponds to the call number of a book in a Wesleyan library. And each book relates to an aspect of the location where the call numbers were placed.

Mr. Schiff and his student team –– Aki Sasamoto, Myra Rasmussen, and James Jacobus –– spent two years researching sites around the campus and Middletown, then matching them to the library records. Some locations were chosen purely for fun, like the communal toaster inside the campus student center, while others try to push you to think seriously about the site.

For instance, Z 711.47.E96 2001, the number on a stone sculpture of a book under the keystone of the arch framing the central doorway to the student center, is the call number for an academic book about the influence of the internet on information and publishing. By contrast, the call number on the exit bar at the entrance to Wesleyan’s Olin Memorial Library, S PQ2637.H82 1956, is for Jean-Paul Sartre’s play “No Exit.”

All this is intriguing, in a bookish kind of way, but is anyone really likely to jot down a call number and then hotfoot it to the library to look it up? Probably not, which somewhat blunts the impact of the project.

Fortunately, the link between the call numbers and their locations is only part of the piece. The numbers also draw attention to the way abstract codes surround us in life. For instance, think of the signs utility workers paint on roads, or the abbreviations for artificial flavoring in food. Most of us know what these things are, but have little idea what they mean.

The installation is one of eight exhibits created by Mr. Schiff and his group for “The Library Project,” a show “exploring the library as an index to the larger world.” The other works are at the Olin library, a Georgian-style building originally designed by Henry Baco in 1923, but completed after his death by the New York firm of McKim, Mead & White.

“Planet” (2003), an ink diagram, dissects categories used to shelve books under the Library of Congress system. In contrast to the Dewey decimal system, which uses a three-figure code from 000 to 999 to categorize the main branches of knowledge, with finer classifications made by the addition of a decimal point, the Library of Congress system groups books by subject, then divides them into sub-categories. The drawing charts these categories and subcategories, and is about the immensity of the library and how you traverse it.

The Same goes for “Yeast” (2003), a diagram beginning from a library computer search for books with “bread” as a keyword. There were seven, each of which contained other keywords that were then investigated, and their keywords recorded. These new keywords were investigated, and another set of keywords recorded. The process was continued until the diagram branched to include thousands of related keywords.

This work’s dusty erudition will no doubt appeal to those for whom the idea of academic research is fun, or art. I admit I do not feel this way, but I was impressed with the finesse of the drawing, which must have taken weeks to produce. I was also intrigued by the random shapes and patterns appearing in the diagram, as if there were another, more intuitive logic at work.

Perhaps the most interesting work is “Number” (2003), a mildly eccentric intellectual exercise derived from Jorge Luis Borges’s story “The Library of Babel.” In the story, Borges provides an apocryphal formula to calculate the exact number of books in the universe. Feeding the formula into a computer, Mr. Schiff and his team came up with a number that, when spelled out, is so big it fills a 500-page book. I wonder, is this new book included in the count?

HARTFORD COURANT, WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBER 24, 2003

The Dewey Decimal Escapade

On Poles, on Cars, Wesleyan Professor Tacks Mysterious Numbers All Over Town

by CORI BOLGER

Courant Staff Writer

Next to the chalkboard menus and above the slabs of meats and cheeses at Neon Deli in Middletown sits a work of art. There’s a similar piece stuck to a tree, and one on the side of an ATM machine at Wesleyan University a few blocks down the street. Somewhere on campus, there’s even art on a toilet.

Since the fall semester began, people have been encountering the art, a random line of letters and numbers that compose an obscure combination, much like the mumbo jumbo on a barcode or an unpronounceable word. They’re in dorm rooms, on trees and in local businesses.

“I see them everywhere,” said Julie Glickman, a senior psychology major.

Although confusing at first, the combinations made sense to Glickman once she found out their purpose. All 500 of the pieces comprise “Index,” an installation project created by Wesleyan art professor Jeffrey Schiff. They’re actually call numbers corresponding to books at Olin Memorial Library and were placed on objects that correspond to a book on a related topic.

A number for a road rage book is on a car. A number about flag burning is on a flagpole.

“Sometimes it’s a little more tangential, or the idea of something humorous,” Schiff said. “And some of them are very direct.”

Even in a place like Neon Deli, where labels and price tags are the norm, the GT2860 R36 2003 on the wall rarely goes unnoticed. Customers point it out to owner Cynthia Galle, who discovered the number refers to the book “How We Eat: Appetite, Culture and the Psychology of Food” after she looked it up on the library’s website a few weeks ago.

“It’s an interesting project,” said Galle, a former english teacher. “It generates interest in the Dewey Decimal system, of all things.”

The project began two years ago, when Schiff and three students came together through grants supplied by the Christian Johnson Foundation. As research, they read several books, including Jorge Luis Borges’ “The Library of Babel,” a philosophical text that depicts the universe as a library, and learned about the origins and evolution of the library catalog system. Next, they began brainstorming for ways to depict the project’s focus –– the concept that the world is our library and the library is our world.

“The world is endlessly complex,” Schiff said. “A condensed version of the world is in the library. At the same time, the world outside is an index of the library.”

The end result is seven art installations, including “Index,” now on display at Olin through Nov. 30. “Index” is the only installation that goes beyond library walls. In downtown Middletown, the number on the wall of O’Rourke’s Diner on Main Street (NA7855 .G87 2000) refers to “American Diner: Then and Now” by Richard J.S. Gutman. At Destinta Theater a few blocks away, the number above the concession stand (PN1995 .75S64 2001) corresponds to “Reel Families: A Social History of Amateur Film.”

To get the project moving, Schiff and his team proposed it to several university committees, including administration and maintenance. They convinced them that the letters used in the project wouldn’t harm school property. Schiff demonstrated this by using several different types of stickers made by the 3Mcompany.

“We realized this is something you can’t just do,” he said. “You can’t use on plaster walls the same thing you would use on sidewalks or glass.”

After the project got approved, Schiff led a “four-day blitz,” when dozens of volunteers fanned into the community with kits and cleaning materials to assemble the numbers. Each of the 500 number locations was digitally photographed and cataloged.

“It was exhausting,” said Myra Rasmussen, a senior sculpture major who helped plan the project. The most difficult part of the task was making sure the number looked good and wouldn’t peel off the object it was placed on, she said.

The numbers weren’t limited to immovable objects. Schiff went so far as to take out an advertisement in the university’s newspaper, The Argus, for a number that corresponds to “Hold the Press: The Inside Story on Newspapers.” On some days, he wears a numbered shirt and drives a numbered car.

At first, Wesleyan students and faculty members were baffled.

“We didn’t want to particularly inform them,” Schiff said. “We wanted them to have the experience of surprise, wonder and not knowing.”

In an effort to keep the numbers from being torn down or switched around, the administration orchestrated a campus-wide announcement via e-mail.

“Now they kind of get it,” he said.